In April 1971, Ian McHarg, a famous landscape architect, gave the Earth Day lecture before the students and guests of Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas. It was a speech that he repeated in numerous venues around the country that year. McHarg had published his landmark city planning book, Design With Nature, in 1970, in which he laid out how cities should be designed with respect for the physical environment, as well as cultural considerations. In this 10,000 word lecture he describes his design approach. He precedes it with a playful introduction of how humans have come to achieve life or death power over the earth.

It’s a youthful audience rather than a professional one, so I’ve decided in the last five minutes to change my subject, and I’ll give a sprinkling of professionalism to those professionals who are here in the last few minutes; but I think it’s probably more appropriate to speak to you on other than ecological planning, because after all you are the generation without any future, and I think it’s probably good to talk about this prospect. You don’t have any future, no assured future at all. And unless you do something about it you face, I suppose, extinction.

It might be worthwhile trying to just simply immerse ourselves into the problem of the environment. The first thing we’ve got to do is forget about the threat of paper cups and Dixie cups and bottles and detergent. The degree of threat that we confront is a much larger one than this. I suppose I became familiar with the dimensions of the subject from a man called Loren Eiseley, a great cultural anthropologist, about a decade ago. Eiseley had an image, the prediction of that time when man would be able to go into space, and in his image he foresaw the time when man from space would be able to look and see this tiny little orb, this tiny little sphere that is the earth, and see it to be green—-green from the maritime algae in the oceans, green from the verdure on land—-and he perceived that this biosphere, this thin film of light that surrounds the earth, gives the image of a green celestial fruit, rather like a lime. And as he looked at it more closely he saw that the green of this earth—green from the maritime algae in the oceans, green from the verdure on land—-and upon this green celestial fruit he perceived blemishes—-pathological tissue, necrotic tissue, morbid tissue, brown, black, gray—-and from these blemishes extended dynamic tentacles, and he perceived that the morbid tissue, the pathological tissue on the world-like body consisted of the cities and works of man and asked, “Is man but a planetary disease?”

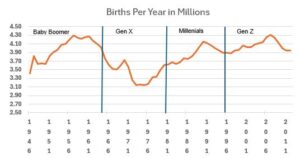

I think that the only proper answer is, Yes, there is a planetary disease upon the earth, and that is man. Moreover, perhaps disease is too kind a word. The real definition of an epidemic is, one creature multiplying at a super-exponential rate, destroying the environment upon which he, she or it depends. All right, if you use that definition for the plague upon the earth, you find, indeed, that there is an epidemic upon the earth, there is one creature multiplying at a super-exponential rate in a process of destroying the environment upon which we depend; the epidemic is man. But it is very important to recognize that not all men or women are coequally epidemics, and so I would say that if you are interested in your future, that it is important that you identify those people who can in fact be defined as epidemics, the people whose continued energies are a threat to the survival of men, and those who are not. Because there is a war afoot, you see, and it’s got nothing to do with this putrescent shame in Vietnam. It has to do with the survival of man, and the identification of those people whose energies are directed to cause the extinction of man. So you must engage in manacling, holding back, somehow muting the extinctionists in order that you can negotiate survival.

Now I have a list of extinctionists, and I’ll offer it to you, irrespective of race, color or creed. I do this as an immigrant Scotsman who has chosen to become an American, but nonetheless I will offer you now, today, my list of the most excoriatable in the United States. Every country should have one of such lists, and all people in the world should of course be dedicated to the survival of man and the muting or manacling of those people who are the extinctionists.

Certainly first on my list are the generals overkill, irrespective of race, color or creed— these men who are able now to kill every single man, woman and child in the world one thousand times over, but who must devote substantial parts of national treasury and, God help us, their intelligence in order now to be able to kill every single man, woman and child in the world two thousand times over. Now these men wake up in the morning and wash and shave and brush their teeth and comb their hair and, God help us, put on underarm deodorant, but they must not be mistaken as men, they are in fact incarnate puss, they are in fact man-planetary disease, man-epidemic. Their fulfillment is our extinction.

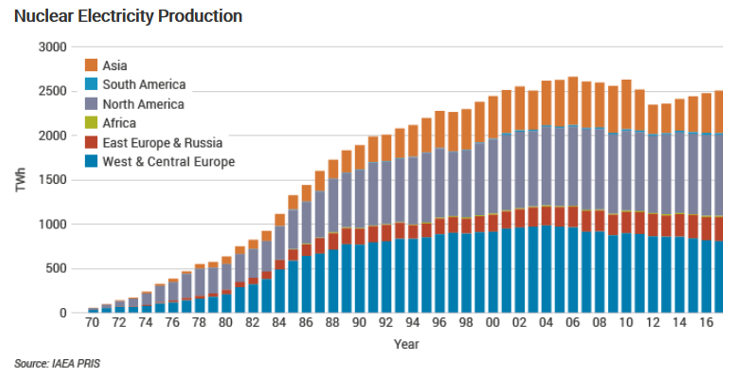

Immediately below them are the putrescencies of the Atomic Energy Commission, the men who started life pulling wings from flies, got to dissecting frogs, made their way up to cherry bombs and then finally realized that high explosives were not enough and that those crippled psyches could only be gratified with atomic explosions either illegally above ground or legally below ground. And they know the first lesson of radiation biology, that every increase in radioactivity has a concomitant increase in the number of mutations and most of these are deleterious. And so indeed every increase in radioactivity is adding entropy or disorder into the most important inheritance of life, which is to say the genetic potential. So, I offer you number two in the list of excoriatables, those people, the Dr. Strangeloves of Atomic Energy Commissions, irrespective of race, color or creed. They attack your gonads, irrespective of race, color or creed.

Number three on the list are a particularly loathsome form of man-planetary disease, those people who are engaged in bio-chemical warfare, the people who feel that the bubonic plague in the Middle Ages in Europe was an effete European failure, and that late twentieth century America can do much, much better with the bubonic plague them poor Medieval Europeans did. And so we have now delegated a substantial sum of money and a large number of scientists to be sure that we can do rather better with the bubonic plague, we can develop a more virulent form, and not only the bubonic plague, but anthrax and botulism and nerve gas which killed sheep in Utah and could have killed people on the way from Okinawa to Unatilla and across the corridor of New Jersey, and other pneumococci of excruciating virulence. These people, again, are, in my opinion, men-planetary disease. Their best energies are devoted to the threat of your survival.

Who next? The people who sell death for money. All the great chemical companies; I believe you have some of them out here, do you? Shell, Monsanto, doesn’t matter who they are, Dow Chemical—-these people who make herbicides and pesticides in the full knowledge that these are toxins, because they are sold as toxic, and they also know they are persistent. and because they are persistent, and gravity obtains it means all these pesticides or herbicides are likely to make their way from land processes to water processes and thence into these great sinks which are the great lakes and the oceans. And everybody now knows that very small quantities of herbicides and pesticides inhibit the capacity of the oceanic phytoplankton, which of course are not only the major food source for organisms of the world but constitute the major source of all atmospheric oxygen. And so, these materials are not only attacking the productive capability of the world, but they are attacking that bubble of atmospheric oxygen upon which we entirely depend. And so I offer you them the biochemical warfare and the pesticide people as expressions of man-planetary disease.

Next I suppose one has got to identify the captains of industry, not because they are really planetary disease, but because they are inflicting so many lesions upon the world-like body, they are so stressing the environment, they have got to be described as having a certain suppurating edge if not more. I had the pleasure of addressing fifty captains of industry in the Four Seasons Restaurant in New York not too long ago. This was the occasion of Fortune Magazine‘s fortieth anniversary. And what masochistic impulse caused the captains of industry to ask me to speak to them is something I cannot explain. But anybody who is a lapsed Presbyterian can at least understand. So there I was, and I went through my list of excoriatables and I got to this point and I said, “Gentlemen, how many of you would describe yourselves as captains of industry?” And forty or so put up their hands. I said, “gentlemen, I wonder if I could make a small bargain with you on behalf of the American people?” And they, having no choice but to assent, assented. So I said, “Gentlemen, it’s very clear to me having seen you at cocktails, dinner, that your personal hygiene is impeccable. There is no doubt in my mind that you wash and shave and use underarm deodorants and brush your teeth and the chances are very good that before coming to this occasion this evening you had another shower, changed your underpants, changed your shirt, changed your handkerchief. I am sure that as American people contemplate your personal hygiene, contemplate as I do your command of knives, forks, spoons, finger bowls, that they would be proud of the personal hygiene of the captains of industry. But I said I wonder if we could make a small bargain. I think the American people would allow some relaxation of your personal hygiene. If you would like to forgo that second shower, second shave, second pair of underpants and shirt, if you would like to burp in public or even fart in public, I don’t suppose the American people would feel terribly badly about it. It’s the kind of problem we can deal with, just so long as, as quid pro quo for this relaxation of your personal hygiene, we have some significant improvement in your corporate hygiene. We can no longer tolerate your voiding hundreds and thousands and millions of gallons and tons of your excrement into our environment, gentlemen. The time has come for American industry to be toilet trained. First, the discomfort of diapers, and then the prospect of continence.” I said, “Gentlemen, are there any representatives of Detroit here?“ And there seemed to be two presidents of corporations there. I said, “Gentlemen, I wonder if I could make a small bargain with you on behalf of the American people?” And they again having no alternative but to sit, sat. I said, “It’s very clear that what America wants from Detroit is modest, non-polluting locomotion. It’s as clear that what we get from Detroit is the most immoderate locomotion, which is gluttonous beyond description in terms of nonrenewable resources, the only efficiency of which is the amount of pollutants it produces per unit of transportation. It produces in fact the maximum units of pollution for the least units of transportation. But,” I said, “it’s very clear just from a cursory examination of your advertisements that you do not believe yourself to be in the locomotion business, the transportation business. You believe yourself to be in the aphrodisiac business. It’s very clear if you look at television or magazines that all the advertisements developed by Madison Avenue for Detroit are really aphrodisiac. They are addressed to men whose genitalia have been atrophied either physiologically or psychologically, and the assumption is that such a poor, atrophied person has only to spend three or four thousand dollars to acquire an automobile, as a result of which he will receive an immediate engorgement of such dimensions that one of the nymphs who is forever pictured in these advertisements will grab him from the front seat of his new car, throw him under the nearest bush and ravish him an ecstasy beyond understanding. Now of course if Detroit could do this, I suppose three thousand dollars would not be too high a price. In the absence of any ability in the direction, could we ask them simply to revert to the business of non-polluting modest locomotion?”

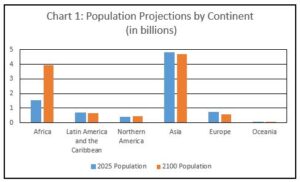

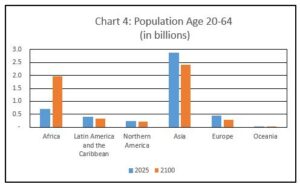

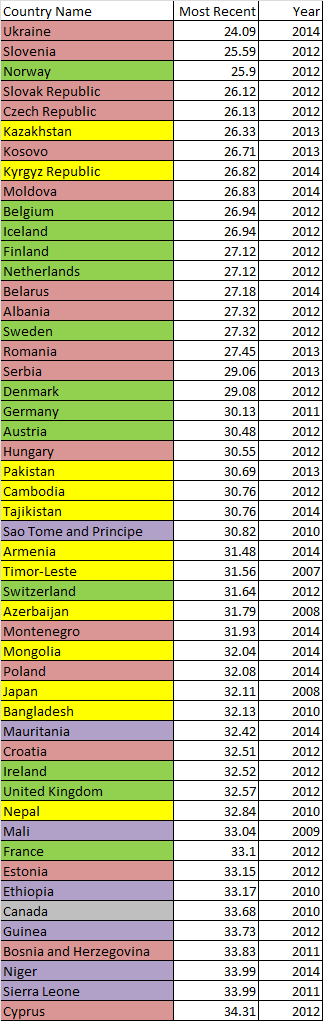

There are also other people we could excoriate, and I suppose I would reserve certainly an important place for Madison Avenue, because here is a place which has made intellectual whoredom a way of life. They spend all their energies to assure us that well-being, that the substance of a man or a woman is in fact only measured by commodity, that is that you are equal to the number of eye-level ovens, electric toothbrushes, electric can openers, electric meat carvers, numbers of horse power in the garage, etc., etc., etc. The substance of a man is only measured by his commodity. Now this of course is a horrifying illusion which can be made to work. That is, if we insist that commodity is a measure of well-being, then we have to accept that three hundred million Americans will not live as well as two hundred million Americans do now live. Moreover, there is no way in which this world can support six billion people at the standard of living of the present three billion people. Absolutely no way! It is a finite world, and the resources of the world are equal to the resources of the world divided by the population. As the population increases, the stress on the environment increases, and the resources available to the population decreases. And this is a truism we better learn. Moreover, of course, it is happily not true that well-being is, in fact, measured by commodity. Well-being is measured by something else —-by one’s ability to look at one’s friends, one’s wife, one’s students in the eye, to have some sense that one’s social role has in fact some social utility. And this being so, then there is a way of dealing with finite world resources without limiting well cu The end of this being show then there is a way of dealing with finite world resources without limiting wealth: That is to change the construction of well-being from commodity into services, so there’s no limit to the fruits of compassion, of justice, of the quality of the physical and cultural environment.. So we must resist as man-planetary disease these people—-Madison Avenue—who insist on our gluttony. As a result of this gluttony we now have to engage in imperialistic wars which used to be done by British and French and Spanish and Dutch, but which are now an exclusively American occupation, the purpose of which is very clearly to rob the rest of the world in order to support the American gluttony.

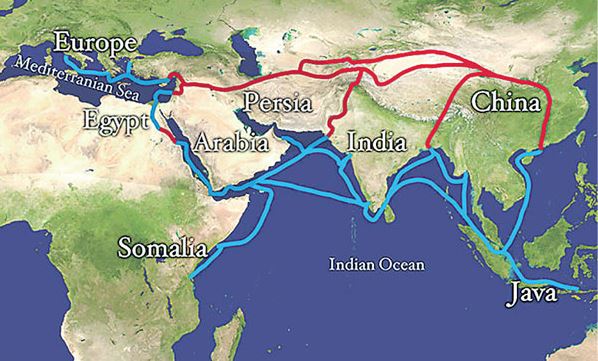

Well of course the general villain in this whole thing is the western view of man to nature, and I think we might pick it up, look at it, avert our eyes in horror, before going on to something else. The fact of the matter is there is only one view. The attitude of man to nature is of course a generalized villain, and this is the only view which is absolutely shared it by capitalists, by communists, by Jew and Christian, by atheist and agnostic. This is the only view which absolutely unites the whole western world. It is in fact bipartisan. The only tragedy about it is of course it has no correspondence to reality, no survival value and is the best guarantee of extinction. And you have, as I have, absorbed it from your mother’s milk, on your mother’s knee, in kindergarten, lower school, upper school, college, university; it permeates our environment, our law, our art, our philosophy; in fact every aspect of our life, our entire ethos, has implicit within it the one view of western man to nature. Now it just so happens that it’s most succinctly expressed in Genesis, and it’s believed by everybody whether they are religious or not religious. And I am very glad to say that my excoriation of this derives not from me, because who would listen to me, but from the most distinguished theologians representing Judaism, Protestantism, Catholicism, that is to say Martin Buber, Abraham Heschel, Paul Tillich, Albert Schweitzer, Gustav Weigal.

Every single theologian has given me the information which I will recount to you in the next two or three minutes, that is, the western view of man to nature is at its most expressive form in the first chapter of Genesis in three statements. The first is, that man is exclusively divine; God made man in his own image. This means there is a moral arena. If you covet your neighbor’s wife or you commit adultery or if you commit theft or murder, God, the courts, the churches, the priests are looking at you and if they catch you at it they’ll rap you right across the knuckles or something worse. If, however, you want to kill every whale, every blame whale, every ponderosa pine, every sequoia, if you want to poison every river, stream and lake and the oceans, apparently God, the church, the priests and the courts don’t give a damn. Because the only moral arena is the acts of man to man, and God is very jealous of these. But the acts of man to nature are not sacramental. God doesn’t care, and so we may proceed to screw up all nature with all the right and the greatest possible profit, without any fear of retribution. And this of course we have done.

The second line says man is given dominion over all life and non-life. Dominion is a non-negotiating term. Dominion is a sergeant major’s view of the world. Dominion says, do it and don’t talk back. We have been given dominion over every creeping thing that creepeth, crawling thing that crawleth, walking thing that walketh, flying thing that flyeth; over every if-ing thing that if-eth hath man been given dominion. So we are given dominion over life and non-life. And the third line tells you the real purpose. The third line says, “You shall multiply and subdue the Earth,” and there are some forms of the Bible, of course, which say you shall multiply and replenish the Earth. But that is such a ringer, and has been such an obstruction to the fulfillment of western man over two thousand years that it has been very properly suppressed, and society has taken to its bosom with all delight and gratitude the injunction to assume exclusive divinity, assume the right of dominion over life and non-life, and assume the role of subjugating the Earth. And if you want to find one text which best explains all the destruction, despoliation, the infliction of lesions upon the world’s life body which has been accomplished by capitalists, communists, Jew and Christian, atheist and agnostic alike, all the people of the western world, throughout all the world–that’s the only text you need to know.

If you want to find another villain who is within this villainy of the western view, that is the conception of man apart from nature whose role is the conquest of nature. If you were a planetary doctor who is responsible for all the planets in our solar system, and you saw there was one planet where there seemed to be a spreading disease caused by one organism, multiplying at a super-exponential rate, destroying the environment upon which it depends, and you picked him up by the scruff of the neck, pulled him off, and said, “Look, Jack, who the hell do you think you are and what are you doing?” He would say, “Don’t you know me? I am Man!” You say, “What’s so great about Man?” He’d say, “Well, you don’t know?” He’d just lift up the top of his head like that and say, “Brain, you see!” Now, I think we’ve got to be a little careful about brain, because you see if there is one creature who assumes that nature exists for his delectation, nature is just a backdrop to the human play, nature is a mine to be mined forever, nature is a system which can be treated any way at all without any retribution, and in doing so he is endangering himself, and he justifies his superiority and his actions on the basis of brain, it would seem there is better evidence for brain as spinal tumor than brain, the apex of biological evolution. I think there is better evidence for brain as being a spinal tumor today, among advanced peoples, than there is for brain being the apex of biological evolution.

I have a small story about this. Once upon a time there was a white-coated, sepulchral, non-combatant warrior. And of course warriors are like that. Once upon time warriors were great big men with double-edged swords, who confronted people face to face. They might have been wrong, but it required a certain amount of knotting of the gut to be a warrior. Today, of course, one is in a basement, white-coated, an abstractionist pressing buttons, and you’re not required to engage in any kind of confrontation at all, which allows me to describe celestial warriors as a sepulchral, white-coated, lily-livered, non-combatant warriors. Anyway, in one of my fantasies, such a person had decided to assume the responsibility for the destiny of all men and all life. He wanted to resolve some temporary, irrelevant, political squabble between the great powers. And he did resolve it, atomically. He pressed some buttons, as a result of which there was a welter of warheads upon the waiting earth, and all life was extinguished in my fantasy. All life was extinguished save in one deep leaden slit, where due to radiation persisted a small colony of algae, little unicellular plants. And these algae in my fantasy perceived that all life had been extinguished save they, and the whole business of evolution, of mutation, of natural selection, of cooperation and competition must ensue—-at least two and a half billion years of this—-had to ensue in order to recover yesterday. And so the algae in my fantasy come to an immediate, spontaneous and unanimous conclusion—-next time, no brains.

That just might be the best conclusion. Nature has been through this thing before. The cockroaches are more ancient than the social insects—-the bees, the wasps, and so on. And somewhere along that line, the cockroaches have a much more highly developed nervous system, sort of a precursory brain, than do their descendants, the bees, and termites and so on. So somewhere nature was through this thing before, as if the cockroaches said, “Look, why don’t we go for this brain thing, it looks pretty smart.” And the conservative, the Republican cockroaches said, “Gee, I don’t know, it sounds a little bit innovative; you know, what was good enough for grandfather should be good enough for me.” And so the cockroaches decided to hell with brains. So they bred out the brains, and they got along with the social insects. The social insects, as we know, the termites and the bees and the wasps, are better able to live with high-density living than any other creatures. And, of course, if we go in for the megalopolis in megaphone high density living as the future of three hundred million Americans, it may very well be we will have to follow the ways of the social insects, only we will do it surgically; that is, we will create an environment which can only be occupied after you have had a frontal lobotomy. It may not be what you expected to hear, but then I have only one obsession anyway.

There has got to be some other view. This view is absolutely calamitous—-man apart from nature, man the conqueror—-because we are the conquerors. It is no accident we talk about the conquest of space, the conquest of the oceans, the conquest of Mt. Everest. Can you imagine some man’s whimpering footsteps on Mt. Everest constituting a conquest? But we talk about it. We are conquistadors. We are so long impugning in the face of an implacable nature that we have been accumulating a bile of vengeance against this nature which was so powerful. And now that we are powerful, we are deciding to wreak our vengeance. And this of course is exactly what we are doing. But we are inflicting lesions upon that life-support system upon which we ourselves depend, as a result of which we are engaging in self-mutilation, which when extended can only lead to extinction.

There has got to be another view. And of course there is another view. And I encountered this view about ten years ago. Oh, I’ve forgotten one very important point. If you think about this extinctionist, this scientist-politician who decided to take upon himself the responsibility for extinguishing all life, if you would have spoken to the man, he would have, I’m sure, assumed that he was exclusively divine, he was given dominion over life and non-life and enjoined to subdue the earth. And in the pressing of the button and bringing upon the earth this rain of warheads, he would be fulfilling his destiny, you see. He would be exercising dominion and subjugation. Now anytime you have a metaphysical view which permeates a society, the fulfillment of which is the extinction of man and of life, then obviously such a view has no survival value, no correspondence to reality, and is in fact the best guarantee of extinction. And I think we have got to recognize this, that we have within ourselves a view which absolutely permeates every facet of our society, all western society, which has no correspondence to reality, no survival value, and is the best guarantee of extinction. And we must replace it; we must find another view.

My first confrontation with this view was about a decade ago when I met a scientist working in Baltimore on an experiment to send a man off to the moon with the least possible luggage. This is a real experiment, and it was paid for by NASA, and it consisted of a plywood capsule simulating a real capsule, in the lid of which was a fluorescent tube simulating the sun, and of course electricity is only fossil sunlight, and who did give the franchises to utility companies to sell old sunlight? Anyway, in the capsule was a fluorescent tube, and inside was some of this algae, little photosynthetic plants in a sort of helical aquarium, and also some bacteria in the same water solution, there was some air and a man. And the system works as follows: the man breathes in some air, consumes oxygen, breathes out carbon dioxide which the algae breathes, which algae breathes out oxygen, which the man breathes. The man becomes thirsty, drinks some water, urinates; the urine goes in the water solution with the algae and bacteria, the algae transpires, the transpirations are condensed and collected and the man drinks it. The man is hungry and eats some algae, and with six billion people in the world most of us will be eating algae, he eats some algae, he defecates; the excrement goes into water medium with the algae and bacteria, the bacteria reconstitutes the excrement into forms utilizable by the algae, which grows, which the man eats. Now this is a beautiful simulation of the world at large. There is one input—-sunlight; the one export—-heat, there is a closed cycle of oxygen and carbon dioxide, a closed cycle of water, and a closed cycle of food. Now, THAT’S THE WAY THE WORLD WORKS! And, as you know, education is a device to produce functional cripples who don’t know the way the world works. Yet this is known to Australian aboriginals and Kalahari bushmen, to Ravidians in Barbary—-all the simple people in the world know this either empirically or they know it rationally, and they live by it. But western society and western education is a device by which this is not known, save five thousand ecologists, probably fifty thousand biologists; it doesn’t permeate our government, our art, our law, our philosophy, our religion, our education. And yet I say to you the man who understands the way the world works has been inside a capsule, knows all he has to know for survival. The man who has not been in there, no matter how sophisticated his information, is a functional ignoramus whose ignorance is in fact an obstruction to our survival. This has got to be understood, you see.

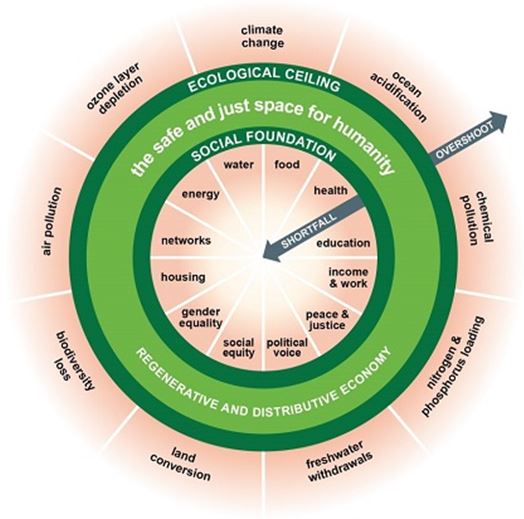

That capsule story absolutely is drastic in its importance. Because all the essential elements are expressed with in it, you see. Man is a plant parasite; only plants can eat sunlight, man cannot eat sunlight. All animals are dependent upon the chloroplasts’ miraculous ability of being able to eat sunlight, transmute it into themselves, which then transmits energy to us. In spite of the illusion of sanitary engineers, no man can in fact reduce waste. Wastes are not reduced by sanitary engineers, who don’t even know the names of the organisms which do it. Wastes are all by micro-organisms, by other creatures. And so, we have got to recognize that we are in fact fundamentally parasites. All the most important world processes upon which we depend are carried by creatures over which we have virtually no control at all, except insofar as we can inhibit them, that is, we can reduce the capability, but we cannot enhance them. As a matter of fact, all of the most important processes in the world are really beyond our control—-the sun, the earth, the orbit of the earth, the inclined axis which gives us seasons, the major physical processes, the evolution of matter, the evolution of life, the eco-systems, the symbiotic relationships between them, the cycle of matter—-all the most fundamental processes upon which we depend are beyond our control and we are entirely parasitic to them. And this of course is not our assumption; we have assumed that nature is just a backdrop to the human play, that evolution is a process only instigated to produce man, that reality consists of a pyramid erected to support man at its pinnacle. We have this infantilism, you see, of man apart from nature, man supreme over nature, man exclusively divine. We have not been in the capsule; we don’t understand the way the world works. Yet we must, because we have got to have a metaphysic, we have got to have a view which corresponds to reality. We can no longer bear this infantilism. It was appropriate when there were only a very, very few men, and where the power over nature was inconsequential. But now when there are so many and we are so powerful, the views that we carry are profoundly consequential, not to nature—-none of us have to worry about the future of nature, nature will endure; the only species we have to worry about, the only endangered species of consequence is man. And so, we have got to find another view which will ensure our survival. I think within the capsule is the beginning of this view, but it’s only a caricature. There is a closed system; there is a finite system—-the earth is a finite system. The sunlight is the only thing which is replaced, and all the matter in the system goes round and round and round and round, and the quality of life is equal to the resources of the world divided by the number of people, multiplied by a coefficient for the rate of turnover. And that’s the implacable truth, and one had better learn this and regulate the conduct of human affairs accordingly.

But of course, this is such a terrible caricature. The world is much more miraculous than this, and in fact the ecological model is so superb. As you know, our current theology is not Judaism or Christianity; our current theology is economic determinism. The only thing wrong with the economic model is it’s partial. That is, it excludes all the biophysical realities; that is, there is no place for the sun, the moon, the stars, the inclined axis of the earth, the seasons, the chloroplast, the cycle of matter or anything else. The economic model excludes every single important biophysical reality upon which we depend. Moreover, it excludes all the most important human aspirations. There is no single place in the economic model for love, compassion, justice, health, happiness, delight or anything else. And so, we have got to recognize it is a very, very imperfect model indeed. We have got to make another one.

We have got to make another one. And of course, there is one ready-made, and it is a beautiful one, much more complete than the economic model, much more elegant, and much more miraculous. This is the ecological model. The ecological model has as its special component the conception of something called creativity. I teach in a school with architects, planners, landscape architects, painters and sculptors at the University of Pennsylvania, and there it is widely believed that creativity is something that artists know about and nobody else knows about. And the way to become creative in the school is not to come to class, not to wash, not to shave, to go into school about three or four or five o’clock in the morning to scratch on yellow paper and canvas. The assumption is that if you work on this hard enough, long enough, late enough at night in a sufficiently perverse way, the god or the muse will touch you on the shoulder and abstract form will appear on the canvas or the paper just spontaneously. And this is called the creative process. Now I think anybody who can make this work should stay with it. Anybody who has got a wire to god or the muse should absolutely stay with it, but there should be another view and another method to be used by the rest of us during the long waiting periods. Well there is.

Creativity is real and true, and creativity can be defined. Creativity consists of the employment of energy and matter to raise matter and energy to higher levels of order. That’s a beautiful definition. So, the evolution of matter up the periodic scale, every proton driven into every nucleus, every electron driven around every nucleus, building up from hydrogen to helium to lithium to beryllium up the periodic scale involve fantastic quantities of energy, the explosions of suns, the explosions of galaxies, in order to drive this creative process of matter from hydrogen to helium to lithium to beryllium all the way up to the heaviest of all elements. And the evolution of compounds was equally a creative process employing energy and matter to raise matter and energy to higher levels of order. The same is true up the genetic scale. Every single step in the scale of evolution of plants and animals, algae, fungi…, every one of those over two and a half billion years of time was a creative process. This, then allows us to say that evolution has been a creative process. Creativity permeates matter and the evolution of matter. Creativity permeates life and the evolution of life. There is no way in which you cannot to be creative, you see. The atom of hydrogen knows about creativity even though man may not. The single-celled animal that is our ancestor knows about creativity even though man may not. Creativity permeates matter and life; therefore, evolution is creative. There is a creative process that has been going on for at least four and a half to six billion years on earth, and within life for about two and a half billion years. Now man is a great destroyer, but it is impossible to believe that God it is so malevolent as to deny man any creative role. That he is a great destroyer there isn’t any doubt. That he may have a creative role there doesn’t seem to be any doubt either. But that he is creative there is profound doubt; there is no evidence that we know of at the moment to show the man is, in thermodynamic terms, creative. That is, engaging in the same kind of creativity that has permeated all matter and all life and all time. But, still, at least we have a concept now of something called creativity, and the challenge obviously is to find a creative role for man which will insure his own survival. If you wanted to use a term to decide whether any process was creative or not, that is, whether a process is a cultural one or a physical one or a biological one, makes no difference; whether we are talking at the scale of your cells or your tissues or your organs or you as an organism, or you as an organism in this room or in this college or in this county or in this metropolitan region or in this country or in this continent it makes no difference; if you wanted to use a term to be able to find out whether the process was in fact creative or not, you would use the term “fitting”. And “fitting” derives two meanings from two different sources. One from a man called Lawrence Henderson, who never made any better than an associate professor at Harvard, but wrote a great book called The Fitness of the Environment. Henderson said, “The actual world, with all its environmental variability, constitutes the fittest possible abode for life, every form of life that has, does or will exist”. On the other side, Charles Darwin said, “The surviving organism is fit for the environment.” Now because the interaction of the environment and the organism is dynamic, and every environment includes other organisms, then you have got to fit the two of them together. And you have got a conception that there is a requirement for every process, be it an idea, or a church, or a school, or a philosophy, or a religion, or an economic theory, or your cells, tissues, organs, or you as an organism—-there is an absolute, implacable, inescapable requirement for that process, every process, to find of all environments the most fit, and to adapt to that environment and/or adapt itself to accomplish a fitting, which, when done, is creative. And the absence of this is a misfit, and a misfit, according to Darwin, will end in extinction. If you want to use a statement, a criteria that is even more synoptic than this, which allows you to look at the degree to which any process, cultural or physical—-it makes no difference—-a city, a town, a house, a person, his cells or organs or an idea—-if you want to use one single term which will allow you to see for any process whether it is creative, which is to say whether it is evolutionary, which is also to say whether it is fit, which is to say that it has been able to find of all environments the most fit and/or adapt to that environment and/or adapt itself, all you have to ask the process is, “Are you healthy?” And if you find any evidence of health—-physical, social, mental—-in human communities—-cultural activities, whatever they are—-if you find any evidence of health, you have found incontestable, incontrovertible evidence that that process has been able to, for the moment at least, find of all environments the most fit and/or adapt that environment and itself. The evidence is in fact the fitness revealed in health. Anytime you find any pathology, whether it is in your cells, tissues, organs, organisms, organisms in an ecosystem, organisms in institutions or ideas, anytime you find pathology—-physical, social, mental, human societies, physiological non-human societies—-anytime you find any evidence of pathology, you have found either temporary or permanent evidence of the inability of that process being able to find of all environments the most fit and/or to adapt that environment or itself. You have a misfit, revealed in pathology. And of course, the perpetuation of pathology will lead to death. That is either the death of a cell; the cell, the tissue; the tissue, the organ; the organ, the organisms; the organism, the ecosystem; or the organism in the community, whether it be the family, or the school, and so on and so on. So here we have it; we have an absolutely beautiful model, in which we have something called creativity, which holds, which is real and true, which is measurable. Fitness is a measure of the degree to which creativity does or does not exist. The presence of creative fitting reveals that health in the one case, the absence of creative fitting reveals a misfit and pathology in the other. Absolutely beautiful model. Now, we also see if we look back at that evolution, which we now have decided is creative, in response to this quest for fitness, has attributes; that is, it always goes from greater to lesser randomness, from simple to complex, from uniform to diverse, from instability to stability (dynamic equilibrium), from a lower to a higher number of species, a lower to a higher number of symbioses, and can in fact in some go from a tendency to disorder towards a tendency to higher levels of order. Now that’s an absolutely glorious model, and you can use that to test anything. If you find yourself with a community which is elaborate, mixed people in terms of income, ethnicity and occupation and so on, in some balanced relationship; and you see this displaced by the process called urban renewal and replaced by suitcase architecture, at the end of which the process has moved from complexity to simplicity, it is retrogressive and reductive; you see, it has produced a misfit. If you find something going from stability to instability over the long term, then you have found something which is retrogressive, you see; it is anti-creative; it is reductive.

So here we have an absolutely beautiful model, and all examinations made by all the most distinguished scientists of this model seem to only confirm it. The ecological model in fact does seem to correspond to reality. And as such, it should become our metaphysical symbol. We can’t just bear to have a model, to have a view of the world, that doesn’t correspond to reality because it will lead us into error and, finally, into extinction. We must know the way the world works. So all of us somehow have got to get into that capsule and understand the fundamental relationships to the major processes in the world, extend this into our metaphysical view, which understands creativity, understands fitness, understands the conception of health and pathology, and seize this as a working model.

I believe that I am engaged in something called creative fitting. I am a landscape architect and a planner; I employ architects and all sorts of other people. But I engage, I believe, in something called creative fitting. The job I do is to try and find, of all environments, the most fit environment for particular land uses or persons, and also to show how these environments, once discovered, have to be adapted and, moreover, how the institution which is selecting the environment has to adapt, either culturally, or by physical adaptations like buildings and places and spaces, but just as well by symbols or by ideas or governmental ideas or economic ideas, it makes no difference. Evolution apparently doesn’t care how you do it just so long as you do it; you can do it by physiological adaptation, you can do it by physical adaptation or you can do it by cultural adaptation, just so long as you do adapt, you do find the most fit environments and adapt these and yourself in order to accomplish a creative fitting, you do it anyway you want.

So, the creative adaptation I am involved in is helping agencies (or anybody who wants me to do it) to find, of all environments, the most fit environment and to adapt that environment and adapt themselves in order to accomplish a creative fitting. How does one do it?

The first thing is we begin by identifying the region itself, because we are going to decide that the region you live in has to constitute your environmental choice. So, how do we describe a region? The first way you start describing a region is to get people who know how to describe it. Now this, of course, is a novelty which is very, very rarely done, because obviously we don’t want to be obstructed by knowledge or intelligence. We want to allow the process to proceed with the greatest amount of stupidity, ignorance and malevolence, as it has been doing in the past, so we can inhibit the largest number of people with the least possible investment of intelligence. But in this particular method we decided we were going to get the people around who actually know what the region is. And so, we get the people who can represent the region as, first of all, phenomena.

And so the people who know this, of course, are geologists, who know about bedrock geology and surficial geology; and meteorologists who know about climactic processes; and we know that we have got to put the two of them together in order to be able to explain surficial geology; that is, the events of the last ten thousand years, which are the most important ones affecting you here, can only be understood in terms of the interaction of bedrock geology and climate. And once you’ve understood surficial geology, then you understand groundwater hydrology because water is where of water is because—-and if you want to answer “because“, then you’ve got to find out the answers from the people who know about climate and bedrock and surficial geology. And once you understand about that then you understand about physiography, because the current state of the earth’s wrinkles is only comprehensible in terms of processes which can be explained from the evidence of bedrock geology, surficial geology, groundwater hydrology and climate. Once you’ve got the physiography then you can begin to understand surface water hydrology because rivers and lakes and streams and ponds are where they are because—-and if you want to answer “because” then you’ve got to find out the information from climate and bedrock geology and surficial geology and physiography and groundwater hydrology. And once you’ve understood that, then you can ask about soils, and soils, of course, are variable and plants know they’re variable; men seldom know they are variable, but they are variable, and if you want to find out why they are variable where they are, then you have to go and ask the people who know about it, which is to say the people who know about bedrock geology, surficial geology, groundwater hydrology, physiography, surface water hydrology, and there are soils because they are only a by-product of other processes. And once you get to that point you can ask about plants because plants are much more variable with respect to the environment than men, and much more discerning; but if you want to know about the variability of plants, then you’ve got to know about the variability of soils, which allows you to know about the variability of groundwater hydrology in physiography and etc., etc., etc. And once you know about bedrock geology and climate and surficial geology and groundwater hydrology and physiography and surface water hydrology and soils and plants, then you can understand about animals, because all animals are plant-related, including that peculiar bipedal animal, man; and if you want to understand about his variability, then you’ve got to find out about the universe of the place in terms of phenomena, because man has been engaged in doing just exactly the same as the others, that is he has been looking for propitious environments, inordinately deep soils, safe harbors or transportation corridors, which of course are physiographic corridors, or the presence of coal, or limestone, or uranium, or oil, or forest, or whatever it is. Whatever he is looking for, the only place where you can find these is in fact in terms of bedrock geology, climate, surficial geology, physiography, hydrology, soils, plants and animals. That’s the universe. But if you only understand it in terms of phenomena and matter or describe it in terms of phenomena, you don’t know very much, because all these phenomena can only be understood in terms of that which has been; that is, that which is now can only be comprehensible in terms of that which has been. And so, one has got to bring these scientists together and ask them to reconstitute all the stuff about phenomena into process, that is, climatological processes, geomorphological processes, fluvial processes, soil processes, and so on, so on, so on. Once you have identified them as processes, you realize that these things are still ongoing. Earthquakes are in fact still working in Los Angeles, the mountains are rising; it’s not a spot to put either an atomic reactor or a hospital. These are in fact real processes. Fluvial processes continue, you see; people will be flooded because the river in fact occupies a floodplain; and anyone who wants to occupy a floodplain in competition with a river is going to lose, the Army Engineers notwithstanding. Anyway, you reconstitute all the information by adding time and you get process; and then, the most difficult thing of all, you bring all these scientists together and you say, “Friends, we don’t care about your little spectrum, your little aperture of reality; we want to see the whole thing as one thing, because there is one thing only divided by language into by science.” And so because I pay them money to do this, and they don’t get paid if they don’t do it, they then reconstitute the whole thing into a layer cake of reality in which the whole thing is causal, that is, it evolved from bedrock geology and then surficial geology and then groundwater hydrology and then physiography and surface water hydrology into soil and plants and animals and micro-climate and meso-climate and macro-climate. There is a layer cake of reality, ten thousand little cells per square inch, and all of these things causal, that is, you cannot explain anyone without explaining any other; moreover, there is an interesting system now, you see, and if you add something at any point in the system, you affect the whole system. Add an atomic reactor at a certain point, and then ask where does the leukemia, skin cancer, bone cancer show up? Add a sewage treatment plant, where does the thermal pollution and the B.O.D. show up? Etc., etc. So you go through the exercise of making an interacting system, which then is an ecological model. You have an ecological model, which simulates reality, which should be a predictive model. Once you’ve got that done you say, “All right, let’s discuss the subject of man, because we are only interested in the environment because of man; you know, it could take care of itself, its only problem is us; and our only problem is us too.” So, we go through the business of trying to find out about man, and we identify man in terms of persons and occupations and age and sex and so on, all the orthodoxy, the dandruff of demography and city planning. Once we identify these as phenomena, we have to identify them as process, because they are only comprehensible in terms of the past; that is, nobody can understand Scotsmen except in terms of masochism and an addiction to poor, thin soils and poverty, because this is the only possible explanation for Scotsmen in Nova Scotia, Maine, northern Pennsylvania, the mountains of Georgia, the Appalachian highlands—-why was it these people always went to areas which guaranteed poverty? So, one has got to ask this sort of question, you see. So, you understand the Germans, Mennonites knew about deep, rich soils, whereas Scotsmen and Irishmen never did. So one has got to go through a business of cultural evolution to find out who the people were, where they came from, what attitude did they have to the land, to fishing, to farming, to mining, whatever else there was, what attitudes they had to law, to government, to religion and so on, what skills they had in adaptation; and then go through a study of the place in terms of the adaptation by people having specific values, but a variable values, to this biophysical field over time, so that once you go through the social process examination, which of course is conducted by cultural anthropologists and ethologists and ethnographers, at the end of this you begin to understand the place as the sum of people and institutions over time who have inherited adaptations felicitous, that is, good, and adaptations which are bad, both in terms of the physical environment and the cultural environment, which in fact allows us to understand the present. And at that point you have a human ecological model. Once you’ve got these two then you are ready to go. Now we have the possibility of a real intelligent planning process.

As you know, the planning process is a sort of tool of the economic model, and its perception really is socio-economic and no more. It wouldn’t recognize a bio-physical process with a label on it.

So given these two layer cakes, one can proceed to the next point, which is of course projection, and we’ve got to be careful about this because the only thing you can say about the people who make projections is that they are remarkably consistent, that is, almost always wrong. But nonetheless, having no alternative but to go the projection route, we go it is explicitly as we possibly can. We make explicit statements about what the conditions are going to be in the future and then project the conditions for that future and we make growth models; we say this group of people are likely to grow into that number of people, consisting of these persons and these institutions and these institutions which demand resources from the future. And so we have reconstituted the area as a biophysical process which has a social value system, and we have reconstituted the people and the institutions and so on also as a social value system, and we can project these into the future and make growth models, one of which should be called an uncontrolled growth model, that is, the face of the future assuming the same amount of stupidity, malevolence, greed and good will going into the future as exists in the present. But we have a number of growth models, and once we have these the idea is to try and accomplish a match; and the best way to do this is use a computer in linear programming. I have a digital scanner at the University of Pennsylvania which allows me to take a map like a state geology map with about seven billion words of information, and I can put these on computer tape in ten seconds, as a result of which I can very easily make this ecological model, and as a result of this I can also use linear programming for resource allocation; that is, if I have information about the region, information about the people, some idea about who the prospective consumers will be in the future, I can then begin to allocate resources according to specific hypotheses. If one hypothesis is the solution of employment, or the true exercise of fair housing, or the elimination of dilapidation or tuberculosis or infant mortality or, on the other side, if we want to ensure that people do not build in flood plains or in earthquake-prone zones or areas which are subject to hurricanes or avalanches, we can set up very explicit hypotheses which are constraints and opportunities for development, and we can allocate the resources to this. We do this by computer. We simply write a program which says the prospective growth by sectors—-low-income housing, middle-income housing, etc., low-density, intermediate, high-density, industry by type, commerce by type, recreation by type—-we can identify these claimants for these resources over time, we write a program and can allocate the resources. And then we can show this; we can show it either in maps, or we can show it in a computer display, or we can show it in a television display; we can display what the alternative forms of the future might be based upon explicit and overt social values. This is the beginning of a process which I describe as an overt, explicit, replicatable public planning process. At the moment, as you know, the planning process is not overt, it’s covert; that is, the Bureau of Public Roads and the State Highway Department hide the highway alignment until the last possible moment, have a public hearing in such a way as to make it very, very difficult for people to oppose, and then they thrust of this bloody highway down our throats – or the Army Engineers, a dam, or the urban renewal agency. Almost all planning at the moment is covert, it is hidden, it is not overt; it is certainly not explicit because it consists of a combination of fiction, good information, bad information, subjectivity and political chicanery, and it certainly isn’t public. So, one would like to replace the present planning process with one in which the information is explicit, substantial and public, that is available. All the information which I spoke about could be displayed on my screen this size—-General Electric has one, which is just a computer screen—-and it should be available to anybody who can type and go to a public library. One should be able to ask for the region to be displayed as phenomena, to have these phenomena interpreted for the utility for man, ask them to display; one should be able to solve specific problems like highway alignment, or such as for systems of open space or housing developments; or identify problems in terms of infant mortality or dilapidation or tuberculosis or anything else. One should also have canned computer programs available to anybody who wants to do them, which will call least social costs, maximum social benefit solutions and by which anybody who wishes to do so may replicate the planning process and come to his own solution. The only thing that the varies is going to be the value system, but the value system then it should be explicit.

All of things are possible now. And I have five more minutes, so I’m going to use my five more minutes to put on a slideshow, about thirty slides, which we can do in five minutes very easily, of a study for Minneapolis-St. Paul, which is only part of the planning process I described. It’s only the ecological planning. But it’s been successful, and I think it has caused there to be the strongest instrument for metropolitan planning in the United States, undertaking perhaps the only ecological planning in the United States. Lights and slides.