“Robots Are Us”

If smart machines replace humans, will “putting people out of work, or at least good work, also put the economy out of business?” That is a question posed by a paper published in February 2015 by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), titled “Robots Are Us: Some Economics of Human Replacement.” The paper deals with the future of employment and income, topics addressed in past posts to this blog. If the few jobs remaining available are low-paying, “Will our self-induced redundancy leave us earning too little to purchase the products our smart machines make?” The model which the authors constructed firmly predicts “a long-run decline in labor share of income (which appears underway in OECD members.)” OECD is the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a group of 34 countries with the mission to promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world.

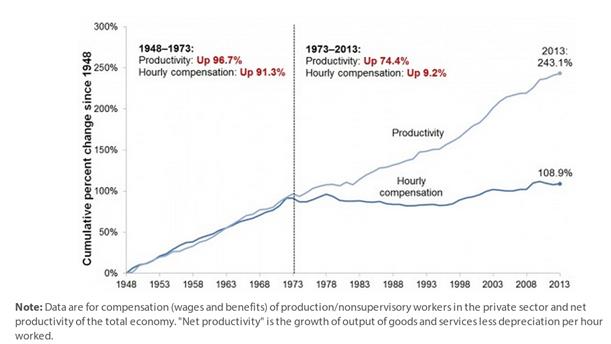

Confirmation of this conclusion comes from the Economic Policy Institute’s analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The disconnect between productivity and compensation is jarringly represented by the graph below. Between 1948 and 1973, productivity and compensation rose in near lock-step. After 1973 productivity continued its rapid increase while compensation was nearly flat.

Martin Ford, in his recent book Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future, commenting on the graph, wrote, “the widening gap between the two lines is a graphic illustration of the extent to which the fruits of innovation throughout the economy are now accruing almost entirely to business owners and investors rather than workers.” While this graph displays trends for U.S. workers, NBER reports that for the 10-year period ending 2013, labor’s share of national income was more precipitous in Japan, Canada, France, Italy, Germany, and China. International Monetary Fund economists studying advanced and emerging economies concluded that “income inequality is a vital factor affecting the sustainability of economic growth.”

The issue goes beyond the question of inequality, a topic discussed in a previous post to this blog (http://fiftyyearperspective.com/examining-inequality/). Economic stability is at risk. As Henry Ford understood when he doubled his workers’ pay in 1915 to $5 per day, without adequate income workers could not buy his products. Getting income into the hands of consumers who have low-paying jobs or no jobs at all has been a function of government-provided “safety nets” for decades, but not on the scale that is envisioned by the above-mentioned studies and others. The next blog post will review the debate over whether a “basic income” for all people is feasible or even desirable.