Congressional District Boundary-setting

“Reinventing American Democracy” was the objective of a 2018-2020 commission by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, involving a broad and diverse group of hundreds of American citizens. The report of the commission is titled Our Common Purpose. Its recommendations for the US Supreme Court were cited in the recent Fifty Year Perspective blog post, Supreme Court Reform.

Among the report’s 31 recommendations, the Commission addressed the process of delineating congressional districts for each state. That recommendation stated: “Support adoption, through state legislation, of independent citizen-redistricting commissions in all fifty states. . . with the goal of establishing national consistency in procedures.”

The method for establishing congressional district boundaries is left to the individual states by the Constitution. In most states districts are drawn by state legislatures. Other states use independent commissions. The process is unavoidably politicized; how lines are drawn can favor one party over another.

In 1812 the Massachusetts legislature created a map with a district that appeared to be in the shape of a salamander. Although Governor Elbridge Gerry was unhappy about the highly partisan districting, he approved the map. Such political manipulation of congressional district boundaries came to be known as gerrymandering. Over 200 years later gerrymandering is still a time-honored tradition practiced by both political parties. Court challenges have successfully blocked some of the most egregious instances.

We have only to look at Massachusetts, the birthplace of gerrymandering, for its consequences. The state has a Republican governor but Democrats control both houses of the state legislature. US congressional district maps are drawn and adopted by the state legislature and approved by the governor to become law.

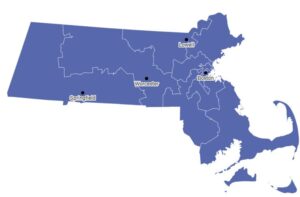

The 2021 redistricting was approved largely along party lines by the Democratic-controlled legislature and signed by the Republican governor. The legislature had sufficient majorities to override a veto by the governor. The first map displays US congressional district boundaries for Massachusetts’ nine districts; blue indicates Democrats hold 100% of the nine seats in the US Congress. (Click on map to enlarge.)

Democratic-controlled legislature and signed by the Republican governor. The legislature had sufficient majorities to override a veto by the governor. The first map displays US congressional district boundaries for Massachusetts’ nine districts; blue indicates Democrats hold 100% of the nine seats in the US Congress. (Click on map to enlarge.)

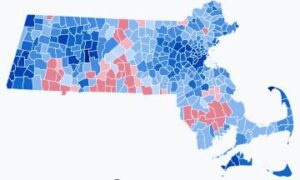

In the 2020 presidential election, the popular vote in Massachusetts was 66% for Joe Biden and 32% for Donald Trump. Biden won in every county in the state. But as shown on the second Massachusetts map, which displays voting in the 2020 presidential election by municipalities, several areas of Trump supporters are evident in red.

was 66% for Joe Biden and 32% for Donald Trump. Biden won in every county in the state. But as shown on the second Massachusetts map, which displays voting in the 2020 presidential election by municipalities, several areas of Trump supporters are evident in red.

Without knowing the density of population in the Trump areas, it is not possible to say for certain that a Republican-leaning US Congress seat could have been carved out. The first district, encompassing the westernmost part of the state, includes many of the Republican-leaning municipalities, yet a Democrat was elected to the seat.

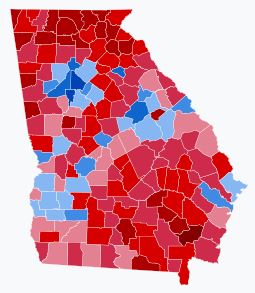

Gerrymandering is alive and well in Georgia. In a state where Biden beat Trump by just 0.2% and both US senators are Democrats, nine of Georgia’s fourteen US congressional seats are held by Republicans and just five by Democrats. The third map illustrates 2020 presidential election results by county. Four of the Democrats represent districts in and around Atlanta, in the blue counties in the northwest part of the state. The fifth is in the southwest corner of the state. The blue counties on the east central part of the state include Augusta. Those mostly low-density counties are divided between two Republican-held districts.

beat Trump by just 0.2% and both US senators are Democrats, nine of Georgia’s fourteen US congressional seats are held by Republicans and just five by Democrats. The third map illustrates 2020 presidential election results by county. Four of the Democrats represent districts in and around Atlanta, in the blue counties in the northwest part of the state. The fifth is in the southwest corner of the state. The blue counties on the east central part of the state include Augusta. Those mostly low-density counties are divided between two Republican-held districts.

The Republican governor and Republican-controlled state legislative houses are in full control of redistricting. The US congressional district map was signed into law on December 30, 2021, and allowed the Democrats to retain a district in southwest Georgia while losing a district northeast of Atlanta to Republicans, for a net loss of one US congressional seat for Democrats.

Redistricting in several states were challenged as illegal gerrymanders prior to the 2022 midterm elections but were used in the elections anyway. Cases have come before state courts in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Carolina, and Utah, and some states may be forced to again reconfigure their House districts. The US Supreme Court, in hearing some of the state cases, will set precedent.

In particular, a North Carolina case now before the Supreme Court (Moore v. Harper) could affirm the “independent state legislature” doctrine, which limits or even bars state courts from overturning state legislatures’ decisions on congressional maps. Should the court affirm the “independent state legislature” doctrine in the North Carolina case, there would be no chance for the independent citizen-redistricting commission recommendation by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences to become a national standard.