Africa’s Outlook

Japan went from rapid growth following World War II to “lost decades,” and China somewhat later displayed similar characteristics, as described in the two previous blogs. Their post-war histories had much in common. One common trend, aging population and workforce, is shared by countries throughout most of the world.

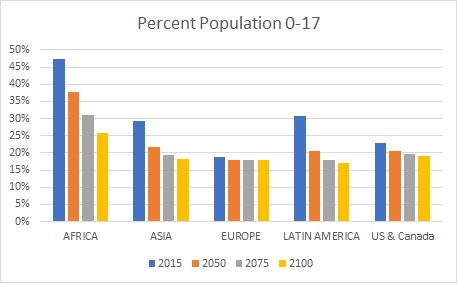

The proportion of the population age 0 to 17 in each of the five continents displayed is projected to fall through the 21st Century. Africa currently has the highest proportion of its population in this age group, 47%; Europe is the lowest at 19%. These United Nations population projections use the Population Division’s medium fertility variant.

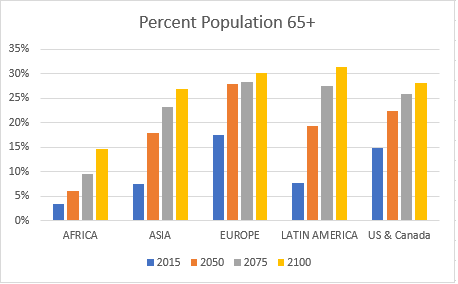

Likewise, all five continents are projected to experience an increasing proportion of their population age 65 and over. While Africa will have a much smaller proportion of its population in this age group, it will experience the highest growth rate, from 3% of its total population in 2015, to 15% in 2100.

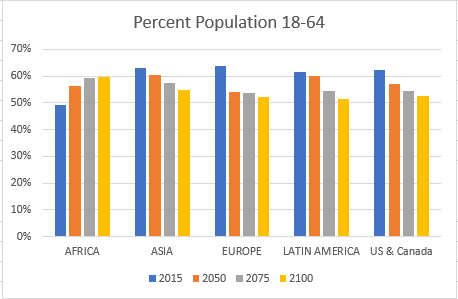

The population between these two age groups, those age 18 to 64, represents the working-age population. For this important age group, the similarity among the continents ends. Only Africa is projected to increase its proportion of population in this age group. The working-age population will decrease proportionately in the other continents.

In 2015 Africa contained 13% of the working-age population. By the year 2100, Africa’s share of the world’s working-age population is projected to increase to 42%. With 16% of the world’s total population in 2015, Africa will make up 40% by 2100.

The diverging trends suggest a number of possible scenarios for the future. While other continents struggle to support their aging population, Africa’s future may lie in providing the goods and services that the rest of the world desires. The more desirable ratio of working-age population to elderly and children should enable African countries to raise living standards on par with other continents. Or African migrants may augment the dwindling work forces in other continents. To cloud the crystal ball further, overlay upon the population trends the uncertain future of automation and artificial intelligence, climate change and anti-immigrant populism. Africa in particular is more likely than other continents to suffer environmental degradation.

These same overlays could alter the United Nations’ assumptions for fertility, mortality and migration. Yet in the end, while Africans have little control over the “externalities,” they will not derive full benefit from a demographic advantage unless they overcome internal issues of disunity, poor governance and corruption.