A Different Kind of Recovery

Recessions are measured in months and relate to decreases in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). A negative growth in GDP, over a period of months, defines the length of the recession. The shortest recession of the last hundred years occurred over six months in 1980. The longest recession since the Great Depression of 1929 to 1933 was the Great Recession, which lasted 18 months starting in late 2007.

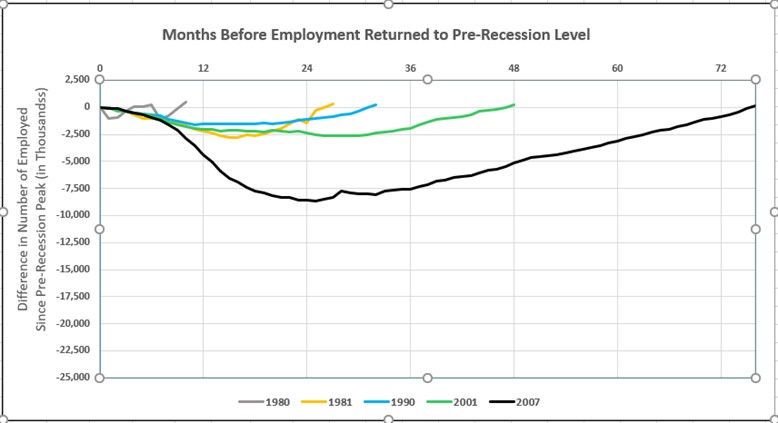

Recoveries from recession are quite another matter. The graph below tracks five recessions from 1980 to 2007, displaying how many months passed before the number of employed workers returned to the pre-recession level. In the 1980 recession, after losing over a million jobs, employment took ten months to rise above the pre-recession level. Later recessions took longer: 27 months for the 1981 recession, 32 months for the 1990 recession, and 48 months for the 2001 recession. Job losses varied from around 1.5 million to 2.5 million.

Then came the Great Recession, earning its title by causing a loss of 8.7 million jobs and taking 76 months to return to its pre-recession level. Note the pattern of each recession taking longer to recover jobs than the previous one.

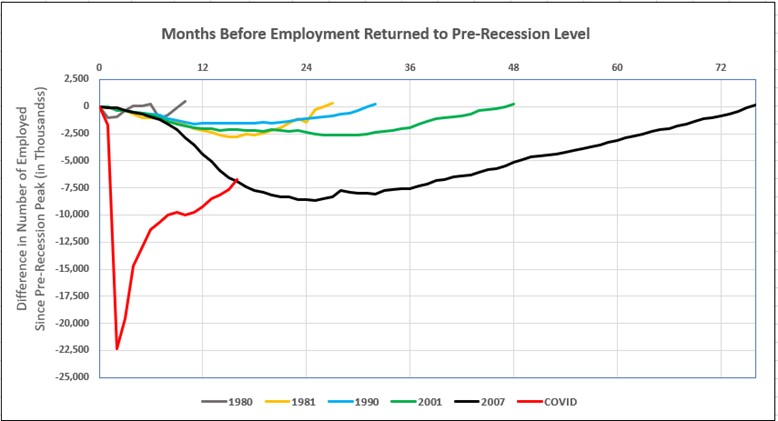

The current recession was the result of the COVID -19 pandemic rather than fiscal policy or inflation. The difference in this recession is that every job that could not be done remotely, or that was not considered “essential,” ended, at least temporarily. Employment dropped by over 22 million jobs in a period of just two months. The hoped-for V-shape recovery hesitated in November 2020, the ninth month, before resuming its upward trend. By June 2021, after 16 months, total employment was still 6.8 million jobs below the pre-recession level, and 9.5 million workers were unemployed.

Response to the pandemic has delayed the recovery. Vaccinations have fallen far short of the level necessary for people to feel secure in returning to jobs. Vaccinations are not yet available for younger children, keeping some parents at home rather than send their children to daycare. Pandemic related unemployment benefits are discouraging some workers from returning to their jobs, jobs they may not have liked because of poor benefits, long, irregular or insufficient work hours, understaffing, or low pay.

But that is only part of the story. Sitting home for several months has given workers time to reevaluate their employment and “work/life balance.” Of the 6.8 million unemployed in June, 942,000 had left their jobs voluntarily, well above figures before the start of the pandemic. With over 9 million job openings in June, workers, whether employed or not, had opportunities to leave for greener pastures. A Pew Research Center study found that two-thirds of the unemployed were considering changing their occupation or field of work.

Clout in the employer-employee relationship is shifting toward the employees. Work-from-home is gaining acceptance; flexibility in establishing hybrid work environments go a long way toward balancing work with family. Employees have recognized the importance of health and safety in their work environments. Wages are increasing generally, more so in jobs in leisure and hospitality. A minimum $15 per hour wage has been adopted by national businesses including McDonald’s, Amazon, Costco, and Target. Applications for new Federal employer identification numbers surged in the second half of 2020 at the highest pace on record, in contrast to sharp declines in new business formation during the Great Recession.

Compared to U.S. workers, Europeans work fewer hours, have longer breaks, and more paid vacations. Don’t expect to receive an out-of-office email like this anytime soon:

I’m away camping for the summer. Please e-mail back in September.

Although you are less likely to receive one like this from U.S. employees:

I have left the office for two hours to undergo kidney surgery but you can reach me on my cell phone any time.