Growth and Decline in World Populations

What at one time seemed a never-ending growth in world population that would eventually overwhelm the earth’s capacity to feed the people, now is presented as a looming population peak followed by rapid decline. United Nations population projections are reviewed and revised periodically to take into consideration current trends in birth rates.

In order for a population to grow, the average birth rate must be at least 2.1 births per woman. Birth rates vary widely from country to country, but they have declined throughout the world. Some of the world’s highest rates are found in Africa, where Nigeria’s birth rate in 2021 was 4.6 and Senegal’s 3.9. India’s birth rate is just above replacement at 2.2, while China’s rate of 1.7 reveals a population that has already peaked.

Current projections of world population anticipate a peak will be reached well before the end of the 21st Century; some projections foresee that happening as soon as the 2060s. As rates continue to fall, population projections are revised downward. The UN 2022 series includes high, medium, and low variants. The medium variant projects a year 2100 world population of 10,355,000,000, an increase of 27% over the population estimate for 2025 of 8,155,600,000.

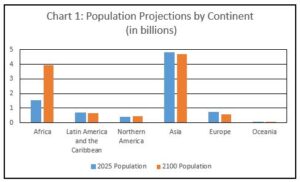

Chart 1 displays the UN population projections for each continent in 2025 and 2100. (Click on chart to enlarge) Three of the six continents are expected to have more people in 2100 than in 2025: North America’s increase is 17% and Africa’s is 159%, more than doubling. Oceania, which includes Australia, is projected to increase 48% to a 2100 total of 68.6 million. Asia is projected to decrease by two percent and Europe by 21%. Thus, in 2100 Africa would represent 37.8% of the world’s population, double its 2025 share; Asia would represent 45.2% of the world’s population, down from 58.9% in 2025. The rest of the world would have 17% of the population.

Chart 1 displays the UN population projections for each continent in 2025 and 2100. (Click on chart to enlarge) Three of the six continents are expected to have more people in 2100 than in 2025: North America’s increase is 17% and Africa’s is 159%, more than doubling. Oceania, which includes Australia, is projected to increase 48% to a 2100 total of 68.6 million. Asia is projected to decrease by two percent and Europe by 21%. Thus, in 2100 Africa would represent 37.8% of the world’s population, double its 2025 share; Asia would represent 45.2% of the world’s population, down from 58.9% in 2025. The rest of the world would have 17% of the population.

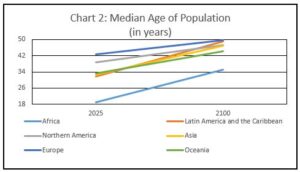

Whether population increases or not, every continent will record a significant increase in median age. Once again, Africa stands out. See Chart 2. Starting from a median age of 19.1 in 2025, Africa’s median age is projected to nearly double, to 35.1. Median ages in other continents vary from early 30s to early 40s in 2025, to mid- to upper-40s in 2100. Europe’s median age will be 49.6.

Whether population increases or not, every continent will record a significant increase in median age. Once again, Africa stands out. See Chart 2. Starting from a median age of 19.1 in 2025, Africa’s median age is projected to nearly double, to 35.1. Median ages in other continents vary from early 30s to early 40s in 2025, to mid- to upper-40s in 2100. Europe’s median age will be 49.6.

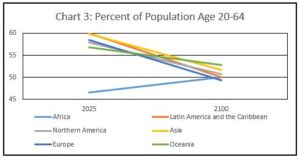

The implications for the Year 2100 labor force are critical. The working age population, roughly 20-64, is shrinking in relation to total population in all continents except Africa. The trend is vividly displayed in Chart 3. Africa’s working age pop ulation is projected to increase both in percent and total number, while decreasing for other continents, with all continents ending between 49% and 53% of total population.

ulation is projected to increase both in percent and total number, while decreasing for other continents, with all continents ending between 49% and 53% of total population.

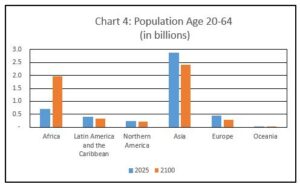

Population age 20-64 comprises an area’s labor force. The sizes of the labor force in each continent in 2025 and 2100 are displayed in Chart 4. In 2100 Africa will have 37% of the  world’s labor force, more than double its share in 2025. Asia’s share of the world’s labor force will be 46% of the world’s total, down from 62% in 2025.

world’s labor force, more than double its share in 2025. Asia’s share of the world’s labor force will be 46% of the world’s total, down from 62% in 2025.

Using data aggregated to the geographic level of continents obscures a host of local variation between countries. China’s median age is projected to be 10 years over Asia’s average, while Indonesia’s will be 2.5 years below Asia. Similarly, Asia is projected to have 52% of its population age 20-64, compared to 46% for China and 54% for Indonesia.

Variations are more extreme among African countries. Central African Republic’s (CAR) 2025 median age of 15.1 years will be well below Africa’s average; South Africa’s 2025 median will be well above Africa’s. By 2100 CAR is projected to increase to 33.9, while South Africa’s will increase to 40.8. Percent of population of working age in CAR is projected to increase from 38% to 60.2%; South Africa’s is projected to decrease slightly, from 57.6% to 57.1%.

Countries with population decline and shrinking labor force place a greater burden on their workers to support government functions. A shortage of caregivers for elderly may occur, and entitlement programs may be difficult to fund, including policies that support children. A deficit of young workers may result in declining innovation. For these reasons, countries in Europe and North America may look to Africa as a source for young workers. That prospect is already on the minds of migration policymakers. Yet European countries display conflicting signals, as “Workers Wanted” signs coincide with barbed-wire border fences. More severe shortages of workers in Europe may change minds.

But those growing populations in Africa have greater potential than to become Europe’s unskilled or semi-skilled workforce. Or worse yet, suffer recolonization under domination of China, which is already a major financier of infrastructure projects in sub-Saharan Africa. With an abundance of universities throughout Africa, the future should offer opportunities for young generations to improve their lives at home.