Blaming the Economists

A business and economics writer, Binyamin Appelbaum, was a Washington correspondent for the New York Times from 2010 to 2019, covering economic policy following the Great Recession. His book, The Economists’ Hour, refers to the four decades leading up to the crisis, during which bankers and lawyers at government institutions charged with policy-making decisions were, over time, replaced by economists of all stripes.

William McChesney Martin, Jr., was president of the Federal Reserve from 1951 until 1970. His disdain for economists was revealed in comments he made to a visitor to the Fed. He said the Fed employed 50 “econometricians” who were housed in the basement because, “they don’t know their own limitations, and they have a far greater sense of confidence in their analyses than I have found to be warranted.” Martin was replaced by President Richard Nixon’s favorite economist Arthur Burns, the first of five economists to head the Fed since 1970.

The most influential economist following World War II was John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946). His disciples believed that the way for government to increase prosperity was to enlarge its role in the economy. A quarter century after the war, economists led a counterrevolution against Keynesian economics, with Milton Friedman leading the charge. They instructed policy makers to maximize growth by “curbing taxation and public spending, deregulating large sectors of the economy, and clearing the way for globalization…” As Appelbaum observes, concerns for impacted workers and the poor were disregarded. Furthermore, “Economists persuaded the federal judiciary largely to abandon the enforcement of antitrust laws.”

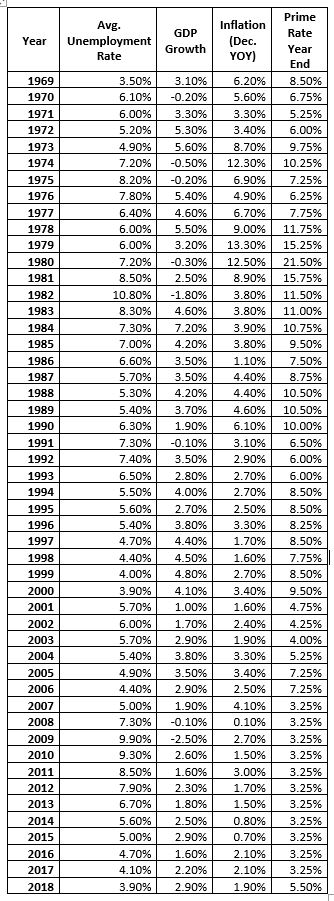

As inflation entered double digits in late 1970s, the new head of the Fed in 1979, Paul Volcker, embraced monetarism, with its focus on manipulating the money supply. Interest rates climbed; “The prime rate – the rate banks charged their best customers – topped out above 20 percent. Consumers stopped buying cars and washing machines; millions of workers lost their jobs.”

President Ronald Reagan followed with tax cuts under the guidance of his economic advisor, Arthur Laffer. Appelbaum wrote “This was a direct attack on the government’s use of taxation as a powerful tool to redistribute income… benefits would trickle down… the promised supply-side benefits did not materialize. Reagan and the supply-siders succeeded in permanently reducing tax rates for those with high incomes.”

When Alan Greenspan succeeded Volcker in 1987, he set out to eliminate inflation. On the advice of the head of the National Council of Economic Advisors, Robert Rubin, President Bill Clinton pushed a tax hike through Congress to reduce federal deficits while restraining spending. “The ‘peace dividend’ from the end of the Cold War made it easier to reduce federal spending; …new technologies drove a surge in productivity and prosperity. By the early years of the twenty-first century, the victory over inflation appeared complete.”

Greenspan harbored “a profound and unshakable conviction that financial regulation was worse than doing nothing.” He succeeded in lowering the rate of inflation, but the benefits accrued to the wealthiest 10% of U.S. household. Lax lending standards of the late 1990s and early 2000s resulted in an abundance of sub-prime mortgages. Financial institutions not subject to the same standards as depository banks packaged and sold sub-prime mortgages.

When prices of mortgage-backed securities fell, the Great Recession of 2007-2008 ensued. Ben Bernanke took the reins of the Fed in 2006, just ahead of the Great Recession. He “pumped money into the financial system until the big banks stood up and started walking again.”

Appelbaum suggests that “The Economists’ Hour … ended at 3:00 p.m. on Monday, October 13, 2008, when the chief executives of America’s nine largest banks were escorted into a gilded room at the Treasury… the government decided to save the financial system by taking ownership stakes in the largest financial firms.” The Obama administration returned to Keynesianism in pushing a $787 billion stimulus plan through Congress… Federal spending on safety-net programs like unemployment benefits also grew rapidly.”

Appelbaum faults economists for lack of attention to the problem of income inequality. Promoting equality through government policy was derided as “inefficient” by some economists. Instead, government policy has effectively done the opposite, increasing inequality. Appelbaum concludes “Willful indifference to the distribution of prosperity over the last half century is an important reason the very survival of liberal democracy is now being tested by nationalist demagogues.”