2500 Years of Globalization

In his recent book, The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, Peter Frankopan writes a history of civilization from the perspective of trade, from ancient times to the present. As the western world debates the value of international trade, this look at 2,500 years of trade along routes linking East and West shows how the quest for resources and commodities shaped global history.

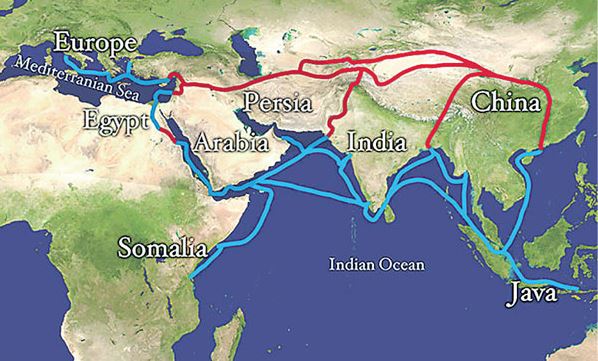

Frankopan writes: “Two millennia ago, silks made by hand in China were being worn by the rich and powerful in Carthage and other cities in the Mediterranean, while pottery manufactured in northern France could be found in England and in the Persian Gulf. Spices and condiments grown in India were being used in kitchens of Xinjiang, as they were in those of Rome. Buildings in northern Afghanistan carried inscriptions in Greek, while horses from Central Asia were being ridden proudly thousands of miles to the east.”

As the cultures along the Silk Road traded goods, they also exchanged knowledge about science, technology, religion, governance, language and war. Might made right, and the riches derived from trade provided revenues to fund military expeditions that brought more resources to the victors. In that regard, trade was no more than a by-product of the quest for power and resources, at times in the name of religion. The history of Eurasian civilization was shaped along the crossroads traveled by Chinese, Persian, Arab, Indian, Turkmen, Greek, Syrian, Roman and Armenian traders, among others.

The rise of the West 500 years ago appears as a result of the replacement of the overland Silk Road by European discovery of ocean routes around Africa to India, and the accidental discovery of the western hemisphere while pursuing a western route to Asia. The latter lined the royal coffers in Europe with gold and silver. The subsequent history of colonialism under European powers extended the quest for resources at the expense of indigenous populations. The German invasion of Russia in June 1941, as depicted by Frankopan, was designed to provide agricultural land for a German population suffering from an inadequacy of domestic food production.

Perhaps the most obvious example of the quest for resources guiding politics in modern history is the requirements for energy generated by oil. Oil has meant rebirth for countries along the old Silk Road like Iran, Iraq and Saudi Arabia. Russia uses its oil and gas resources to apply political pressure on Northern Europe and Ukraine. The manufacture of mobile phones and laptops depend on availability of rare earths found in Kazakhstan.

What Frankopan calls the New Silk Road consists of railroads and oil and gas pipelines running east and west across Eurasia. He describes the 7,000-mile international railway connecting Chongqing, a city of ten million in southwest China, to a major distribution center near Duisburg, Germany. Half-mile long trains make the journey in sixteen days. Frankopan asserts “the use of energy, resources and pipelines as economic, diplomatic and political weapons is likely to be an issue in the twenty-first century.”